Hello everyone. I am on the road again, for the third time in 2015. I am intending to spend just under 3 months exploring much of Greece, though my first week has left me a little shaken. I flew Sept 16 from the US through Amsterdam directly to Thessaloniki, 2nd largest city in Greece. The Greek operated flight of the last leg was delayed in Amsterdam 4 times, without explanation, putting me into Greece about 4 hours late. Otherwise the trip was the usual series of long flights and challenging airports. I am staying in a decent hotel right in the heart of the old city, within a couple blocks of the seafront.

The negative event, that has me a little shaken, was a successful pickpocket effort made as I was exiting a crowded city bus returning from visiting the archaeological museum. The thief, or thieves, struck when the bus was crowded at the town center and I was trying to exit. I knew I had been jostled heavily, but kept firm hands on my pack and camera. Within seconds, however, I realized that it was my closed front pant pocket that had been targeted. They got my wallet with perhaps around 400 Euros, but most importantly a couple of debit cards. This brought back memories of Barcelona where 6 years ago my backpack was hit for a bunch of cash and my passport – I was stuck there for 10 days awaiting a replacement passport. I have for many years split my cash and cards into separate places so I never lose everything, and secret my passport deep in my day bag (in most countries, including Greece, one is expected to always have the original passport available for inspection by police). That worked well for me here, as I had left most of my cash and my other credit card locked in the hotel, and the passport was protected. However, I strongly desire at least one of my debit cards for ATM cash replacement, and so am again stuck, this time in Thessaloniki, awaiting replacement cards. I have found all the international toll free numbers, the national toll free numbers and/or the collect call phone numbers, which the banks provide for such emergencies, DO NOT WORK either from cell phones or hotel phones (at least in my hotel). What a pain. The numbers do work from the rare, derelict and grimy few remaining public payphones out on the very noisy street. Otherwise one is left calling the bank’s local non-toll free number internationally – from my hotel that set me back 107 Euros, charged at 2 Euros/minute. From my international cell phone sim card service, 24 out of the 27 calls to the banks got dropped within less than a minute – always while waiting for some computerized answering service to run through its program – really really frustrating. I will laugh heartily about this after I return to the US and give a piece of my mind to the two financial institutions involved, regarding the complete inability to easily and effectively get a living person with whom to talk. Anyway, one replacement card, Ally, is scheduled to be delivered to my hotel tomorrow, just under a week from the theft. The other card, from Vanguard, has not even been re-issued yet.

Back to the good stuff. Wow, is the food ever terrific here. My guide books talk about restaurants (estiatorias), which are expensive and open very late, but I have not seen one. Instead, the little streets and alleys here in city center are lined with tavernas and ouzerias (basically taverns and ouzo joints) where most of the people seem to congregate for food and drink. They all spill into the streets as sidewalk cafes, and only really fill up after 8:30 pm or so, though open all hours. A majority of the items on the menus are appetizers, ala carte plates, mezedhes, etc., basically large plates of hors d’oeuvres. I have tried at least a dozen different dishes, and all are just excellent, if not quite cheap. These include very lightly crusted fried calamari, zucchini or sardines, various roasted dishes of eggplant and wine & leak roasted meats, as well as a huge variety of cheeses and salads. All of the places also serve great house wine (in the range of 3-5 Euros for half a liter) and small 200 ml bottles of the terrific Varvalianni ouzo. A little different is the very popular Turkish type grill cafes, where grilled meats and sandwiches are very cheap and filling. The grocery store nearby sells me very decent red wine at 1.75 Euros per liter, which blesses my late afternoon pre-meal reading sessions out on my room’s little balcony overlooking the major Tsimisky Street.

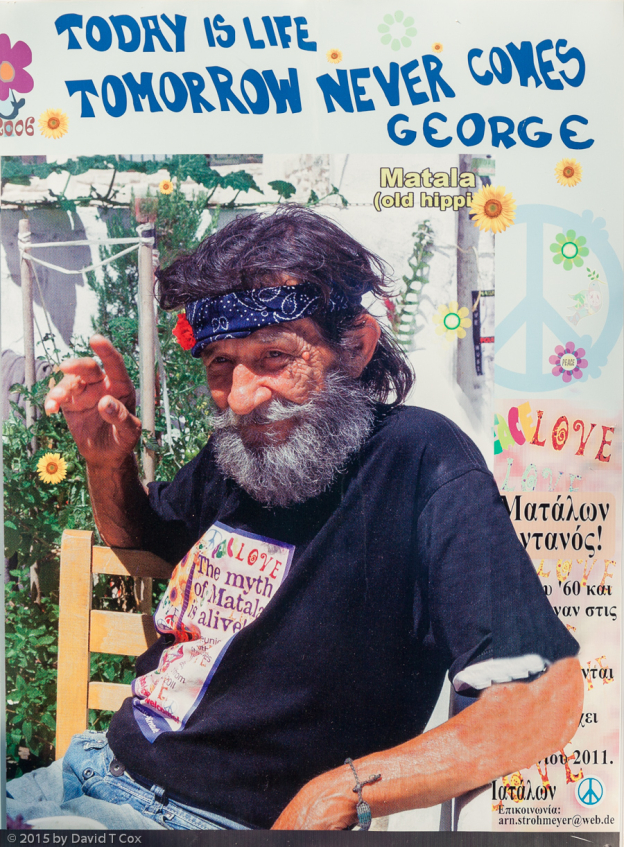

My first full evening in Thessaloniki was Saturday over a week ago, the day before the national elections (in which, surprisingly to me, Tsipras again pulled out an easy victory); I was late going out to eat, when a major political protest march passed by my hotel and my outdoor cafe. The thousands of marchers, mostly seeming quite young, carried black and red banners, and my restaurant owner said he thought it was the Anarchist Party. I have included a photo (but note the party did not get the necessary 2% vote in the elections sufficient even to have a single representative in government). I also have included two photos of myself seated in two different, but by now favorite, sidewalk ouzerias, one with house wine and the other with the great Varvalliani Green ouzo. These are actually pre-supper drinks – I really do eat my full meals at the same places.

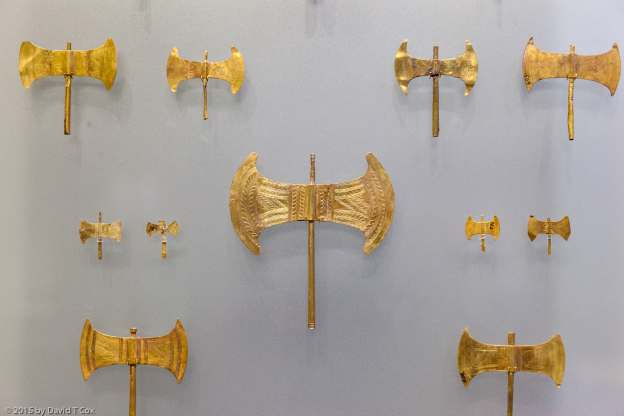

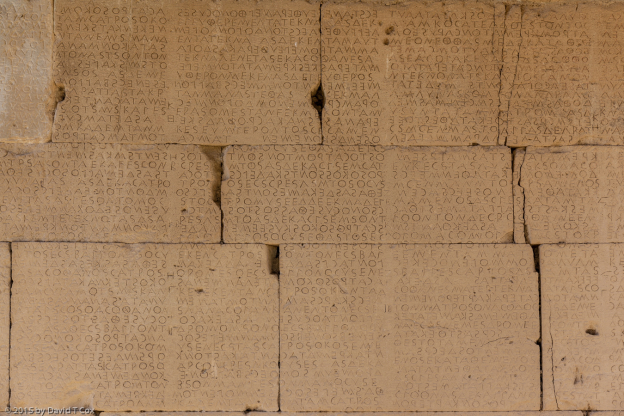

I have spent close to 4 full days, not successively, wandering the streets of old Thessaloniki viewing ancient sites. The city was founded shortly after Alexander the Great’s death, around 320 BC, and named for his half sister. It first was a major Hellenistic capital in Macedonia, after Pella, then a fairly major regional city under Roman rule between 146 BC and 330 AD, where several Roman Emperors, including Galerius, lived. It became the second capital of the Byzantine Empire, alongside Constantinople, from 330-1453. It fell to the Ottoman Turks with the sacking of Constantinople in 1453, until liberation in 1923. In short, its ruins include Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman. Funerary artifacts from the region include also much older bronze age, archaic and classic Greek period objects.

No Hellenistic ruins are within the city, though numerous tombs with funerary goods have been found all through the region. These are displayed in the wonderful Museum of Archaeology. The earliest architectural ruins within the city are from the Roman period, and include the Arch of Galerius, the Galerius Palace, the Agora or Forum and the round Rotunda, which was converted to use in the 4th century as the first Christian church of the Byzantine period, and then subsequently to an Ottoman mosque in the 15th century. Starting from the 5th century, Byzantine churches were built throughout the city, and many of the oldest remaining churches in the world are here. A number of 5th century churches are still in use today, and many contain remnants of 5th through 8th century mosaics and frescoes. The Ayios Sofia is modeled after the church of the same name in Constantinople (Istanbul), though smaller. It dates from the 8th century, though it has been heavily restored since then. The 5th Century Ayios Dhimitrios serves as the city’s basilica, and contains the oldest 5th through 8th century mosaics and friezes. Under the church one can visit the crypts where Saint Dhimitrios was imprisoned and martyred. The oldest church, built as a church, is the Panayia Ahiropiitos, built in the 5th century, which contains wonderful intricate carved capitals on the marble columns, and remains of mosaics on the undersides of the arches.

Parts of the Byzantine defensive walls remain along the mountain crests in the high parts of the city, and where the walls used to reach the sea still stands the White Tower, the final defensive part of the system, and now the symbol of Thessaloniki. Also there are a number of bath houses and other structures from the period of the Ottoman Turks rule. The Ottomans actually converted a number of the Byzantine churches into mosques, which within the last 100 years have been converted back into churches.

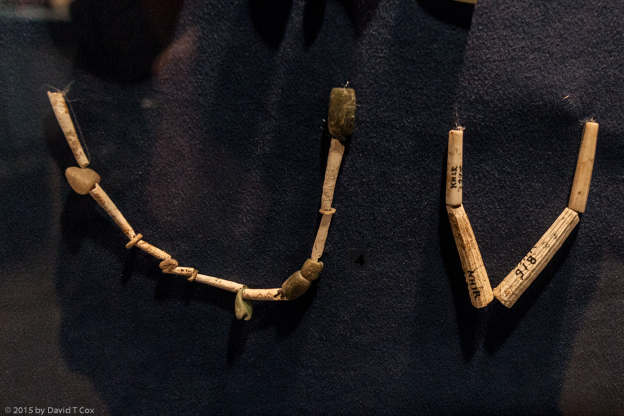

Last Monday I traveled by bus to the small community of Pella, where lie the ruins of the second capital city of the ancient Macedonian Kingdom, 4th century BC through the Hellenistic era, around 2nd century BC, which Kingdom culminated in the rule of Philip II who conquered and united all of Greece. His son, Alexander the Great, who conquered the rest of the then-known world, was born and raised in Pella. The ruins are considered less than 10% excavated and known, but the site museum has a trove of wonderful objects. Some of the private house mosaic scenes are famous, and this is where Aristotle spent his final years teaching (including Alexander as his most famous pupil).

Last Friday I traveled by bus to the city of Veria, and from there to the tiny hamlet of Vergina – from the 6th to the 4th century BC called Aigai, this was the first capital city of the Macedonian Kingdom, and here lie the very recently excavated Royal Tombs of Aigai, which include the Macedonian Kingdom style rock-cut tombs of the royal families, including most famously that of Philip II. The “museum” actually exists underground under the giant earthen “tumulus” mound which covers the royal tombs. Inside one can see the entrances to 4 of the royal tombs, with their sealed marble doors set between false pillars and under friezes with paintings. The contents of Philip’s tomb are quite astounding, including large amounts of gold, military weapons and metal and ceramic containers and artifacts. Unfortunately, for me, this appears to be the one museum in Greece with a “no photography” rule, so if you wish to see any of the artifacts, you will need to search the site on the internet. Back in Veria I visited its local Archaeology Museum which houses a terrific small collection of funerary artifacts from the Macedonian Kingdom tombs which lie everywhere under the modern city. I was here most impressed with the terracotta female figurines, which to my eyes look just like Victorian porcelain figurines – I suppose these Veria figures provided the model.

I hope to receive one of my two replacement debit cards tomorrow, and probably will not wait for the other; I feel the need to move on, as I will have spent almost 2 weeks in Thessaloniki. I think next I will head down to the small village of Litohoro, on the side of Mt Olympus where the Gods reside. I may not climb the mountain, risking the anger of Zeus, but hope to visit some nearby ruins and a castle, before moving on to central Greece. Later. Dave

PS – I note the longer captions under the photos below are being cut off – however, if you click on any photo, the slideshow displays the full captions, as well as a much better view of each photo.

- Dave at Kazaviti Cafe with house cask wine, Thessaloniki Center near Hotel Le Palace, Greece

- White Tower, Byzantine walls fortification terminus, Thessaloniki, Greece

- Anarchist Party march, Thessaloniki, Greece

- Arch of Galerius, Roman Emperor Galerius, 298 AD, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 11 story grafiti, buillding at corner cafe street, Thessaloniki, Greece

- Dave at Marathos Ouzeria with bottle of Varvalliani Green Ouzo, Thessaloniki, Greece

- intricate capitals and mosaics, Church of Panagia Achiropiitos, Byzantine 5th C, oldest church in Thessaloniki, Greece

- Church of Panagia Chalkeon, Byzantine 11th C, Thessaloniki, Greece

- Bronze helmet w gold mask, funerary goods, Archontiko Necropolis ca550 BC, Pella Site Museum Exhibition Macedonian Treasures, Greece

- original mosaic of Lion hunt, Dionysos House Pella, Helenistic Greek culture, 325-300 BC, Pella Site Museum, Greece

- Colonnade of Dionysos House, Pella, Macedonian capital city, 325-300 BC, Greece

- marble bust thought to be Alexander the Great cult statue, 175-200 AD, Museum of Archaeology, Thessaloniki, Greece

- gold blossomed myrtle wreath, Central Macedonia 350-300 BC, Museum of Archaeology, Thessaloniki, Greece

- Derveni Crater, bronze funerary urn, 330-320 BC, Dervini Grave 2, Museum of Archaeology, Thessaloniki, Greece

- marble sarcophogus Dioniysian scene, with inscription “if somewone were to open it, he will pay a fine ti the sacred treasury, Thessaloniki, West cemetery, mid 3rd C AD, Museum of Archaeology, Thessaloniki, Greece

- eastern Byzantine walls looking toward sea, Ano Poli quarter, Thessaloniki, Greece

- mosaic 5th – 9th C, Agios Dimitrios Church, 5th C Byzantine, Thessaloniki, Greece

- terracota figurines from Macedonian rock cut tomb 56 in Karadomanis Plot, 2nd C BC, Veria, Archaeological Museum of Veria, Greece