Hello everyone. I have started a several month long road trip, hauling my little Scamp RV to the western US – at least 6 National Parks in California I never have visited, plus a number in the northwest I wish to visit again.

My drive started Monday Mar. 28, a hot dry day in Tucson. I drove the short distance directly west to the tiny “town” of Why, Arizona (couple of houses, gas station, tiny reservation casino). The only “restaurant” closed at 4pm. The casino (room with some slot machines, no players) had a snack bar but the fryer was down, so they only had a microwave to heat some prepackaged hamburgers from the fridge. I drove the 15 miles north to the small mining town of Ajo to find dinner. Why stop in Why? Because it is the closest RV park to the Organ Pipe National Monument. Organ pipe cacti are one of the 4 types of giant columnar cactus, along with the Saguaro, Cardon and Senita, all of which occur only in the Sonoran Desert of southwestern Arizona and northwestern Sonora, Mexico. Unfortunately, the weather chose a very rare rain day as I drove through the Monument; cool but not conducive to photography.

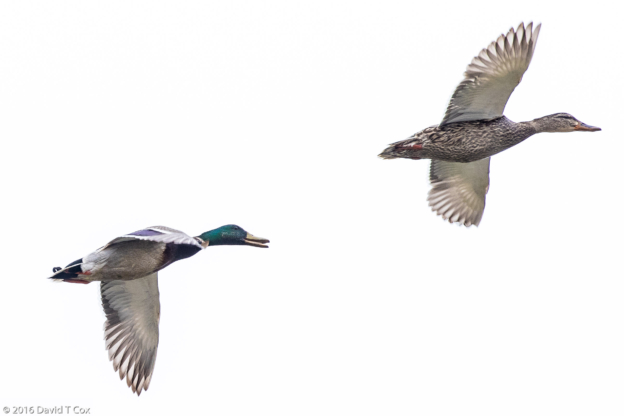

From Why I drove northwest up to the Colorado River just south of the Parker Dam and Lake Havasu, an area called The Parker Strip. For about 20 miles, on both the Arizona and California side of the river, the river basin is lined with communities and resorts, including the Colorado River Indian Reservation, many homes with back porches constructed as private boat docks onto the river. Nestled halfway up the Arizona side is the wonderful Buckskin Mountain State Park, right on a huge bend in the river, with plentiful trees and full RV hookups and facilities. I hiked out to the turn-of-the-last-century copper mines which dot the mountain tops east of the river. The 30 and 40 foot deep shafts of the mines along the trails have been fenced to keep people from stumbling into them. The almost barren hillsides were completely devoid of any wildlife or birdlife, although the riverside had an abundance of birds, almost all European “trash” imports (common worldwide, such as European starling, Eurasian collared doves and house sparrows).

From southern Arizona I drove to my first major destination, Joshua Tree National Park in southern California. Although I had done some research into what to look for and to do, somehow I missed the fact that from the end of March to the middle of April is the absolute high season for both this park and Death Valley, apparently due to the nice weather, the spring flower season and the California universities’ spring breaks all coinciding in time. All 7 campsites in the park were full, outside RV parks were booked through the middle of April, and hotels were booked. I got the last room, one night only, in a motel in the town of Joshua Tree. The Park Service told me this time of year always is busy, but this year is breaking all records – they have not seen such crowds before. I enjoyed one 5 hour early morning drive through the loop encompassing the best of Joshua Tree, with a number of fine views, but very little in the way of any wildlife. The Joshua trees themselves, for you unfamiliar with them, are the signature plant for the Mojave Desert, as is the saguaro cactus for the Sonora Desert. Joshua trees are simply one of many species of yucca plants – they are called “trees” because they happen to have such large stalks, and multiple branches, that fully grown ones actually are “trunked” and branched up to 35 feet in height.

Because of the overflow at Joshua Tree, I called ahead to Death Valley National Park for reservations, and found the same situation – all campsites booked and full. I found a private RV park site just at the western edge of the Park, in Panamint Valley, with an opening for one night only on the upcoming Sunday, 3 days in the future, which I reserved on the spot. I drove north from Joshua Tree to stay for a couple of days in Mojave. I was amazed at the extensive wind turbine power plant starting just north of town, and similarly amazed two days later driving up to Death Valley at the two huge solar power plants just to the east of Mojave.

My RV park in Panamint Valley was desolate (this pretty much describes all of Death Valley National Park outside of the mountain tops). Panamint Valley is the valley just west of Death Valley itself. On a different subject, Tucson AZ has the cheapest gasoline prices in the US (always). California the most expensive. So I was not surprised at finding prices rise from $1.70 to around $2.70 upon crossing into California. Driving north into the desolate reaches of the Mojave Desert to reach Death Valley it did not surprise me much to find the California prices jump from around $2.70 to about $3.40. This price held true even inside the Park – except at one pump – the one where my RV camp was – there the private owners jumped the price to $4.50. Finally, at that price I was willing to accuse them of price gouging. Fortunately, I could avoid that pump and so paid “merely” $3.50 further inside the park.

Most of Death Valley itself lies below sea level, and due to the triple range of mountains to the west, is robbed of all moisture laden air which would drop rain; it averages less than 2 inches per year. This year it had fairly decent winter rain, following good seed dispersal in prior years, so this was a blockbuster wildflower year. Crossing the two 6,000 foot mountain ranges, to the west of the valley itself, provided a profusion of roadside wildflowers. Even below sea level, the roadsides were colored in many places with flowers. Much of the valley floor itself at the lowest levels is sheets of white alkali salt flats, as well as alien landscapes of giant broken chunks of salt-mud composites created as the ground swells and shrinks with the infrequent rain and baking heat. The end of March temperature while I was there was a cool 97 degrees Fahrenheit. Again, the lowlands were devoid of wildlife during my visit.

From Mojave I drove north 6 days ago to Three Rivers, just outside of Sequoia National Park. The drive up through the southern Sierras was beautiful with wildflowers, and the long drive on small highways through much of the San Joachim Valley presented miles of citrus and nut groves. Three Rivers sits at the junction of two forks of the Kaweah River, in a lush valley at the base of the Sierra Nevada Range. I stayed at the Sequoia Ranch RV Park, with its large family flock of very noisy acorn woodpeckers, constantly swooping to the thousands of holes drilled into the various tree branches to insert acorns.

Upon driving the small winding road up into Sequoia National Park, at around 7,000 feet one finds oneself inserted into the heart of the largest of a string of Sequoia groves, the Giant Forest. The sequoia tree is shy just a few feet from being the tallest tree species on earth (the Redwoods are slightly taller on average), and the sequoia is within a few feet of being the largest in diameter (girth) at the base (the baobab trees of southern Africa bear that record), but, because the sequoia trunk maintains so much of its massive girth for almost its entire height, it is the largest tree on earth, and, indeed, the largest living thing on earth. Viewed from some distance, and in isolation, the trees do not appear as truly massive as they in fact are. Once one stands next to the trunk of a very mature sequoia (very mature taking thousands of years and achieving trunk diameters of between 20 to 30 feet) the scale at the base becomes obvious. Standing at a distance, the overall effect, where the sequoia stands among its much more numerous various pine species, is that of some sort of alien construct, an aberration built among the normal forest. The trees reach full height of between 250 and 300 feet at about 700 years, at which point the very tops die back and become rounded and any remaining lower limbs fall off, leaving a massive columnar trunk rising 250 feet into the sky, the first 150 feet of which is barren of branches. Then, over the next couple of thousand years, the trees simply continue to grow in girth, until they exceed in size all other living things – Magnificent!

I spent one day driving north to the neighboring Kings Canyon National Park, which contains more sequoia tree groves, including the perhaps best single spot for public viewing right around the Grant Grove parking lot. While there I did manage to photograph a beautiful male Audubon’s warbler (subspecies of Yellow-rumped) and a raven scavenging for nesting material.

Back at Three Rivers my RV campground filled up for the weekend, apparently partly because that is when people from the coastal cities head for the parks, and partly because of a Jazz Festival occurring over the long weekend. I inquired about attending some of the festival, with sessions at a number of close-by locations, but the $40 per day ticket price dissuaded me, along with the approaching multi-day rain moving in.

The night before last it started raining, and is supposed to continue raining throughout central California for about 5 days. Yesterday I decided to leave the Three Rivers area, where the rain would have had me stuck inside my RV in a crowded campground, and drove up to Groveland, at 4,000 feet in the Sierra Nevada, a tiny old gold-rush town outside the entrance to Yosemite National Park. Here I found an RV park with practically nobody in it. Even with the rain, it is a fresh treat. The Iron Door Saloon in town claims to be the oldest continuously operated drinking establishment in California, being established sometime during one of the two local gold rushes of the 19th century. Surprisingly, it served me quite a good breakfast this Sunday morning.

Tomorrow am is supposed to be rain free so I intend to make my first visit into Yosemite. Until later. Dave

- Dave camping with Scamp at Buckskin Mtn St Park, Parker, AZ

- Buckskin Mtn State Park, AZ

- Eurasian collared Dove, Buckskin Mtn St Park, Parker, AZ

- Joshua Tree, Joshua Tree NP, CA

- Mesquite Sand Dunes, Death Valley, Death Valley NP, CA

- Badwater Basin, 282 ft below sea level, Death Valley NP, CA

- Devil’s Golf Course, Death Valley NP, CA

- wild flowers along Hwy 14, west of Death Valley NP, CA

- Acorn Woodpeckers, Sequoia RV Ranch, Three River, CA

- Sequoias along Big Trees Trail, Sequoia NP, CA

- Lodgepole Chipmunk, Brg Trees Trail, Sequoia NP, CA

- Dave Cox before Sequoia, Big Trees Trail, Sequoia NP, CA

- General Sherman Sequoia, largest tree in world by volume, Sequoia NP, CA

- Common Raven with nesting material, near General Sherman Tree, Sequoia NP, CA

- wildflowers, Sequoia NP, CA

- Acorn Woodpecker, Sequoia RV Park, Three Rivers, CA

- California Quail female, Sequoia RV Park, Three Rivers, CA

- Yellow-rumped Warbler (Audubon’s), Grant Grove, King’s Canyon NP, CA

- Four Sequoias, Hwy 198, Sequoiia NP, CA