Hello all. I last wrote from Chania reporting on Crete and the very ancient Minoan civilization. From Chania I flew on the 24th back to Athens for one evening. The day I arrived in Athens, a huge police presence had blocked off a commercial street 2 blocks from my hotel; turns out a bomb had been detonated in the middle of the night in the Association of Industries Building, apparently by a radical political party averse to large business. The insurance adjuster, with whom I spoke as he was waiting for the forensics team to let him in the building, told me the bomb had been called in 15 minutes before detonation to ensure the building was evacuated, and had done only damage to the improvements. Early the next morning I flew on to Larnaca, Cyprus.

In Larnaca I stayed at the nice Hotel Achilleos with its good buffet English breakfast (includes fat sausages, baked beans etc.). The first afternoon, after purchasing a sim card to obtain a local cellphone number, I visited the Agios Lazaros Church, originally constructed in the 9th century, and said to be built over crypt and tomb of St Lazarus, the very one and same said to be raised from the dead by Jesus. Tradition says he fled to Kition, the original name of Larnaca, Cyprus, and, after being appointed the first bishop of Cyprus by Paul, died and was buried here, only to have his remains removed to Constantinople 900 years later (like the fate of the chryselephantine statues of Olympia & Athens Acropolis). Anyway, the Church is very nice and full of little ladies lighting candles and kissing all the icons and images of various saints, including Lazarus.

The next morning I took the Intercity Bus from Larnaca half way to Limassol, where I got off near the World Heritage Site of Choirokoitia (pronounced Kirokiteeya with the accent on the “tee”).

Cypriot Recent Aceramic Neolithic Culture

Warning: If you do not wish to read a fairly long exposition on a 7th Millennium BC culture, tracing its development extending backward to the ice age, skip this section. I am utterly fascinated and delighted by being able to connect the farmers and herders, who constructed a walled stone-age town, back to their ice age progenitors. I have not found this information easily available in any single document, but have pieced it together from various archaeological information signs posted at the site, together with information from several different artifact displays at two different museums, plus internet research. The major source of information comes from a large poster, detailing the culture, on the wall of the Neolithic Room in the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia.

Choirokoitia is the oldest major village site found on Cyprus, dating to the early Neolithic around 7,000 BC, and was abandoned around 5,500 BC. The community is fascinating in that the village construction is so advanced, built by a culture now called the Cypriot Recent Aceramic (without ceramics) Neolithic – which occupied the island from about 10,000 to 5,000 BC (nine other sites have been identified as being of the same culture and time period). The people practiced animal husbandry with goats and pigs (and cattle with ancestors at a nearby site), and farmed a variety of cereal grain crops. Only partially excavated, visible in the village now are the lower remains of the walls of some 80 circular rooms (hundreds must be unexcavated), the basic architectural unit, with stone and mud brick walls constructed up to 1 ½ meters thick at the base, with inside diameters of from 2 to over 7 meters. The interiors often were further partitioned for various purposes. Evidence was found for flat roofs built of clay upon a thick wood thatching, fragments of which are in the Larnaka District Museum. The circular rooms were arranged into larger groupings forming houses consisting of several rooms around small common communal areas outside. The entire village, with its very dense packing of structures, sits on steep slopes straddling the top of a small mountain. Several dozen human burials were found under the floors of the circular rooms, indicating perhaps continuing relationships with ancestor spirits. Together with the burials often were artifacts and occasionally juxtapositioned animal remains.

Most impressive, the village is surrounded by perimeter earthen and brick walls (from 2 different periods) with stone facings, of almost 300 meters in total extent. The walls were up to 4 meters in height, with a single entrance; the entrance to Village 2 penetrated the outer wall with a series of 3 sets of stairs set at right angles to each other, requiring a sharp turn and climb inside a narrow opening beside an inner second wall, finally entering the village against the wall of a building. This pattern suggests clearly, to me at least, a defensive purpose. It took some powerful social organization and cohesiveness to create the pattern of houses with stone walled circular rooms, and to construct the massive community perimeter walls with defensible entrances; this greatly surprised me, realizing this village was first constructed almost 9,000 years ago, double the age of the First Kingdom of Egypt from whence came the pyramids. I generally pictured stone-aged peoples of 9,000 years ago as living in caves or wood-framed pit houses covered with thatch or animal skins, not in plastered stone-walled houses in villages with huge perimeter walls. In the attached photos, I have included some examples of the sophisticated stone goods, and an absolutely unique anthropomorphic bust of clay.

I also have included a photo of a unique 9,000-10,000 year old zoomorphic bust made of serpentine, with feline features, which came from Parekklisia-Shillourokampus, a nearby earlier period site of the ancestors of Choirokoitia, which was occupied from about 8200 – 7500 BC. The bust is a remarkable and beautiful piece. The site had collective human burials in designated areas, often positioned with intact animal burials; these reportedly are some of the earliest such burials in the world. One recent excavation of a burial found a cat in association with the human burial, suggesting the earliest known domestication of cats, far earlier than that at Egypt, and, to me at least, supporting the identity of the serpentine piece as representing a cat. Dogs also were domesticated. Evidence from genetics suggests that certain cereal grains were first domesticated in Cyprus at this particular site. Remarkable also are the presence of domestic cattle remains at this site, and also at an earlier site (9000 BC) named Kissonerga-Mylouthkia. Cattle were not among the native fauna of Cyprus, and so had been imported from the mainland by these very early Aceramic Neolithic peoples at this time. Cattle disappear from the record by the time of Choirokoitia, suggesting to me that cattle husbandry could not be sustained (domestic cattle reappear in the record around 3000 BC). Also in this early phase, around 8200 BC, obsidian, imported from Anatolia (Turkey), was used for blades – evidence of trading with the mainland. Obsidian disappears from the excavations, replaced entirely by local flint and chert, by the time of Choirokoitia. Structures in the earlier settlements were of wood within perimeter trenches. Both Shillourokampus and Mylouthkia had a number of deep, circular, man-made water wells, up to 25 feet deep to reach underground streams, with built in hand and foot holds down the sides. At the earlier Mylouthkia site one human skull, buried in one of the well structures, clearly displayed cranial deformation with flattening of the occipital, a custom found on the nearby Asian mainland (also common in Mesoamerica 8,000 years later). In the latest phase of Shillourokampus, the architectural units began to become curved stone walls, presaging Choirokoitia.

The Cypriot Aceramic peoples first arrived on Cyprus around 10,000 BC (12,000 years ago), and occupied a rock shelter site called Akrotiri-Aetokremnos, about 40 km west of Shillourokampus. Cyprus was home then to dwarf elephants and pygmy hippos, which survived at the end of the most recent glaciation, and bones of both were found at the rock shelter, the hippo bones together with the strata of human artifacts; many of the hippo bones showed burning, though no evidence of cuts. Experts have debated “hotly” whether the arrival, at the end of the Pleistocene, 12,000 years ago, of the ancestors of the Cypriot Aceramic Neolithic culture, was associated with the extinction of these creatures.

Absolutely fascinating, to me, is starting with the of arrival of man on Cyprus, near the end of the Pleistocene; then being able to trace these people through early settlement formation, the domestication of animals and importation of cattle, domestication of cereal grains, production of very sophisticated stone ware, and gradual evolution of architecture to the multi-use circular building units, cohesively arranged into housing units, within a town with huge perimeter stone walls, and defensible entrances, at Choirokoitia. The culture seems then to have disappeared around 5000 BC (over 1,500 years before the start of the Mesopotamian, Indus Valley or Egyptian civilizations), but perhaps future work will reveal a continuation, or connections with subsequent cultures.

End of Cypriot Aceramic Neolithic Discussion

The day after visiting Choirokoitia, I visited the recommended Pierides Museum in Larnaca, a private foundation museum for display of the extensive archaeological collection of the Pierides family, mostly accumulated during the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. As with most such collections, this one was started with the claimed purpose of preserving on Cyprus the ancient artifacts extracted for sale by tomb robbers. It seems to me that these large private archaeological collections simply increase the value of the trade in stolen ancient artifacts, thus supporting and expanding such trade. The sad result is that these artifacts never can be properly placed in context. Further, the sites from which the objects were removed are irrevocably damaged for further study. Finally, because so many of the artifacts are sufficiently unique and in relatively good shape, questions must invariably arise regarding authenticity. Similar museums I have visited include Amparo in Puebla, Rufino Tamayo in Oaxaca, Mimbres pottery collections in Deming & Lordsburg, the Gold Museum in Lima, and Popol Vuh in Guatemala City. The Gold Museum was exposed 20 years ago; up to 90% of the “precious” Peruvian artifacts being viewed as fakes by investigators.

I did a walking tour visiting several areas of Larnaca where excavations have revealed the sanctuaries and walls of the ancient city of Kition, a major center during Hellenistic and Roman Periods, and also visited the little Larnaca District Archaeology Museum which had several stone vessels and roof fragments from Choirokoitia.

On Saturday I traveled by bus from Larnaca to Limassol which sits on the central southern coast. The first afternoon I hopped a local bus west to the Kolossi Castle, a medieval tower built by the Order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, aka Knights Hospitaller, Knights of Malta, Knights of Rhodes or just Hospitallers. This was one of the two powerful Catholic military orders of the medieval period of the crusades (the other order being Knights Templar). I previously reported on Old Town Rhodes, where the Hospitallers had their headquarters for two hundred years. Prior to acquiring Rhodes, and after losing their base in Acre in northern Israel to the Arabs in the 12th century, they briefly established headquarters in Cyprus and built the initial Kolossi castle; it was destroyed over the intervening 300 years by earthquakes and various attacks, and a new castle was built in the mid 15th century which stands today. I particularly admired the single small closet sized outer room on the 2nd upper floor which served as the private toilet of the Master. From the outside I could see the extruding drain which would have carried the waste outside the castle walls.

Sunday the 29th I traveled by bus to Ancient Kourion, a great Hellenistic and Roman Period city just west of Limassol. The area actually was first populated during the 12th century BC by the Mycenaeans, and remained a center through the Greek Dark Ages, Archaic Period and Classical Periods, but all structures which are visible today are from the Hellenistic and later periods (after 325 BC). The Roman Nymphaeum, Stoa and Agora create a great jumble of walls and columns, and on one side are great areas of Baths, with the underground water systems visible today. The most interesting remains, to me, are the two great houses of late Roman design (early Christian period 4th C. AD), both of which contain well preserved mosaic floor designs left in situ (much better than removal to a museum – of course one must accept huge modern roof structures overhead to protect what has been exposed). The site of Kourion is spectacular, sitting on the edge of low limestone cliffs overlooking the southern Cyprus Mediterranean Sea.

While waiting for the return bus from Kourion, sitting on the bus-stop bench under trees in the middle of nowhere, a half grown kitten took a liking to me; I stroked it for some minutes, and then it would not leave me alone. While I sat on the bench, it proceeded to climb all over me, draping around my neck, up over my head, and down my back returning to my lap. I finally got up and stood several feet from the bench; it stood on the bench mewing pitifully at me for some minutes, then took a great leap landing on the left side of my chest with four paws splayed and 20 sharp claws extended to catch itself on the verticle surface. OW! OW! OW! That hurt, and brought little spots of blood traced onto my shirt. I did not consider taking that kitten home with me.

On Sunday the 30th, a rainy day, I traveled by bus from Limassol to Paphos on the southwestern coast of Cyprus. It has a very pretty old-town promenade along the sea and harbor, but most of the town seems deserted now; except for the restaurants facing the sea, the streets are lined with dozens of closed taverns, sheesha houses, discos, bars, restaurants and car rentals. Apparently they simply shutter the doors from October through sometime in March.

Nea Paphos (New Paphos) is the “new” ancient city which grew massive from the Hellenistic through the Roman Periods (about 325 BC through 300 AD – the old city of the Archaic-Classical age lies to the north). The central Agora (market), theater, Asclepion and a number of homes have been excavated overlooking the sea at the very southwestern corner of the island. At the south side of the ancient city are several “villas” of astounding size, with dozens of rooms with extensive floor mosaic designs – all left in-situ. The House of Dionysus covers 22,000 sq. ft., with the mosaic floors covering 6,000 sq. ft. of the villa. That represents enormous wealth. Large protective buildings have been built over the sites to protect the now exposed mosaics. This is the densest collection of mosaics I have seen, and many are stunning. I particularly liked the Mosaic of baby Dionysus in Hermes lap, surrounded by a number of personages, the five panel-mosaic in a room of the House of Aion, and the Mosaic of Icarus in the House of Dionysus, photos of all of which are included below.

Several kilometers north of the villas and the Agora are the “Tombs of the Kings”; it is in fact one of the cemeteries of the Romans of ancient Nea Paphos, where the very wealthy had entire “houses” carved into the limestone rocks to serve as tombs. In arrival at some of the tombs, one is confronted with an opening into the ground, and looks down into a solid stone courtyard surrounded by verandas behind carved stone pillars. Upon climbing down steps into the tomb, the “courtyard” is surrounded by underground rooms carved into the soft sandstone in which are various chambers where the dead were laid to rest. All artifacts, of course, were looted millennia ago. Nea Paphos, Old Paphos and the Tombs of Kings together are a World Heritage Site.

On Wednesday I traveled to Nicosia, capital of the island, which lies in the heartland on the border between the Republic of Cyprus, recognized by the UN, and all nations but one, as the legitimate government of the island, and North Cyprus which, for 45 years, has been governed and occupied by Turkey. After decades of strife, the border now is easily crossed, and as of this year, new talks are underway by both sides which may ultimately lead to some lasting resolutions to the old conflicts. I spent several hours yesterday on the Turkish side of the border, after an easy crossing where only a passport must be shown going either direction. The Selimiye Mosque (originally the St Sophia Cathedral), built in 1208-1326 AD, is a marvel of Byzantine-Gothic-Ottoman construction mix.

I visited for 3 ½ hours the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia; it is reputed in many sources as the must-see archaeological museum in Cyprus, and highly recommended. It was a let-down. I did get to see the available artifacts from the very earliest culture, the Cypriot Early Aceramic Neolithic, discussed above, which established Choirokoitia 9000 years ago. The museum certainly has a number of nice pieces, including from Kition and Nea Paphos. I will not dwell too much on its short-comings, but the lighting was very bad, with little spot beams inside small glass cases which shone like the sun on narrow spots, leaving the rest in darkness. Little was labeled, and much that was labeled often identified artifacts as “from various”, or “provenance unknown”, or listed half a dozen sites without telling what was from where. A majority of artifacts apparently were donated or on loan from various private foundations or families; this emphasizes the sad fact that the majority of great Cypriot ancient pieces have been pilfered over the last two centuries by grave looters, gathered into various private collections, and what has been recovered or donated now makes up the bulk of the museum’s pieces. I intend no blame for the curator or country; the fault almost certainly lies with the political chaos that Cyprus has endured for a couple of hundred years.

I have delighted in the evenings, while drinking wine on my balconies, in watching the small insectivorous bats which whirl through the air around the buildings of the coastal towns. I watched what I believe to be the same bats in Rhodes, and by my recollection they are identical to the ones that amused me 10 years ago in the southern ancient Roman port of Antalya, Turkey. These were replaced, to my astonishment, in Nicosia which lies at the interior of the island, with large flocks of wagtails, which would circle overhead after sundown, calling constantly, reminding me more of the common swifts of the western Mediterranean. Without binoculars or my long lenses, I am uncertain of the species. I never have seen wagtails congregate in this manner.

While in Cyprus, I have been eating often at Kebob Houses, which are common in the western Mediterrenean. They serve up not just kebabs, but dozens of various grilled dishes and veggies, at very reasonable prices. The last two days the weather finally broke, and turned cold (50 degrees F) and windy. I have been spoiled with sunny beautiful warm days for almost 3 months, with only a handful of rainy periods.

Today I have returned to Larnaca from Nicosia. Tomorrow I fly back to Athens for 3 days, and probably will again visit the Archaeology Museum – a world class museum. On Wednesday I depart for the long return trip to Arizona. I reflect back that on the island of Crete, studying the MInoans, the oldest link in Western Civilization, I feel I completed my archaeological trip through Greece. On the island of Cyprus, I have been able to examine one of the oldest sophisticated cultures in the world, and trace it back to the Ice Age. I apologize to those of you who would rather see photos of birds and wildlife. I will return to that hobby soon. Dave

-

-

Agios Lazaros Church and Tomb, 9th C, Larnaka, Cyprus

-

-

circular buildings modeled after originals, Choirokoitia ruins, 7th-6th M BC, Neolithic village, Cyprus

-

-

Choirokoitia ruins, 7th-6th M BC, Neolithic village, Cyprus

-

-

sophisticated stone vessels, Choirokoitia, 7th-5.5th M BC, Cypriot Early Aceramic Neolithic, Cyprus Museum, Lefkosia, Cyprus

-

-

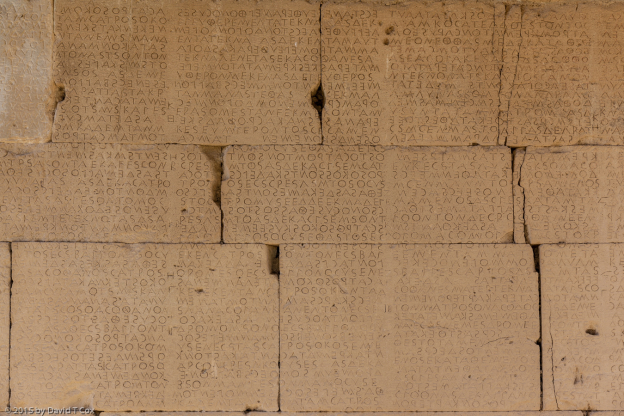

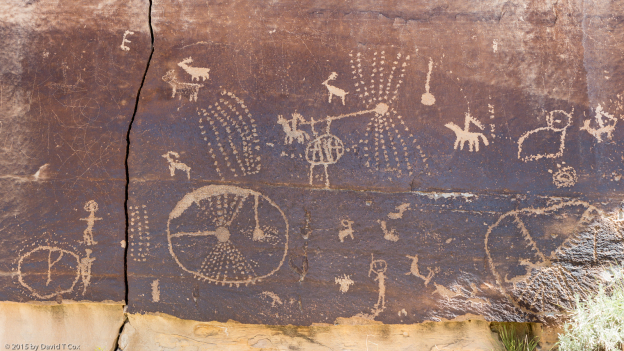

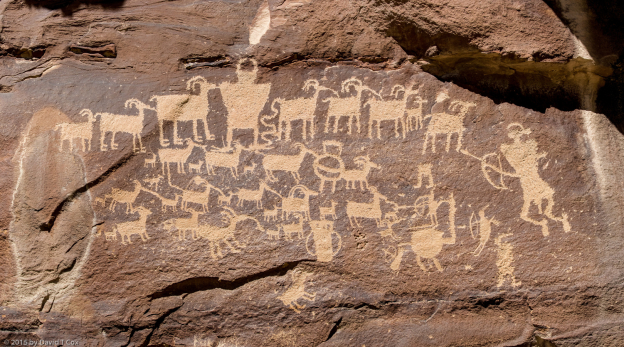

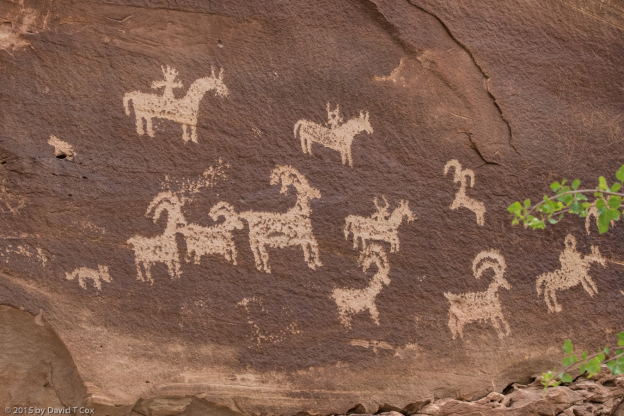

engraved stones, Choirokoitia, 7th-5.5th M BC, Cypriot Early Aceramic Neolithic, Cyprus Museum, Lefkosia, Cyprus

-

-

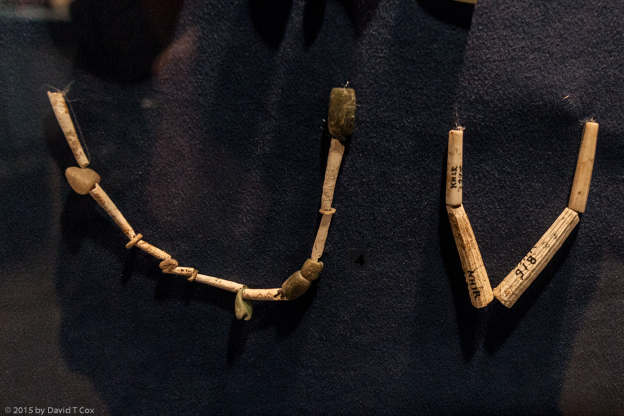

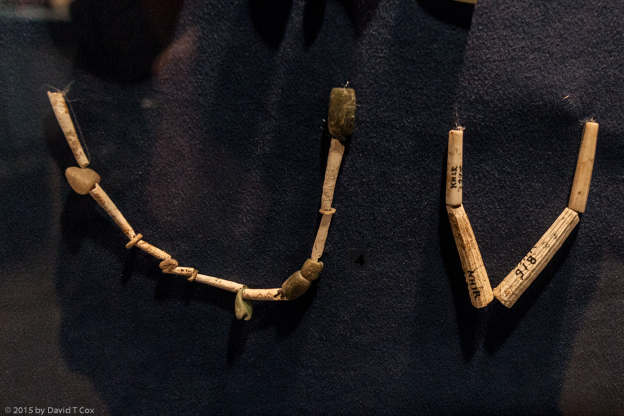

necklaces of dentalium shells and beads, Choirokoitia, 7th-5.5th M BC, Cypriot Early Aceramic Neolithic, Cyprus Museum, Lefkosia, Cyprus

-

-

clay anthropomorphic figurine, Choirokoitia, 7th-5.5th M BC, Cypriot Early Aceramic Neolithic, Cyprus Museum, Lefkosia, Cyprus

-

-

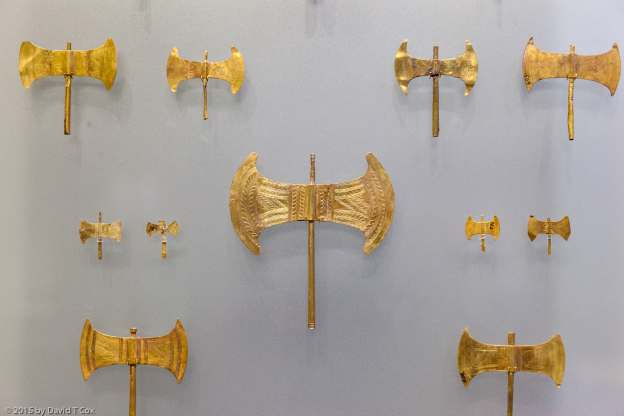

pendants of picrolite, chalcedony and diabase, Choirokoitia, height of Aceramic Neolithic culture, 7000-5500 BC, Cyprus Museum, Nicosia, Cyprus

-

-

serpentine head figurine w feline features, funerary artifact, pre-Choirokoitia, Cypriot Aceramic Neolithic Culture, Parekklisia-Shillourokampos, 8200-7500 BC, Cyprus Museum, Lefkosia, Cyprus

-

-

obsidian, flint and chert blades of pre-Choirokoitia culture, Parekklisia-Shillourokampos, 8200-7500 BC, Cyprus Museum, Lefkosia, Cyprus

-

-

Kolossi Castle, 1454, Order of St Johns of Jerusalem, Limassol, Cryprus

-

-

Roman Stoa, early Roman to 4th C AD, Kourion, Cyprus

-

-

fisherman on dock, Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Tomb 3, Tombs of Kings, World Heritage Site, Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Tomb 3, Tombs of Kings, World Heritage Site, Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Tomb 7, Tombs of Kings, World Heritage Site, Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Tomb 4, Tombs of Kings, World Heritage Site, Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Tomb 5, Tombs of Kings, World Heritage Site, Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Rain over sea from Tombs of Kings, World Heritage Site, Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Mosaic “Baby Dionysos in Hermes lap”, House of Aion, Nea Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

House of Theseus, Nea Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

House of Theseus, Nea Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

part of Mosaic “Icarios and Dionysos”, House of Dionysos, Roman, late 2nd – early3rd C AD, Nea Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

central part of Mosaic “The Triumph of Dionysos”, House of Dionysos, Roman, late 2nd – early3rd C AD, Nea Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Mosaic dog chasing Mouflon, part of “Hunting Mosaic”, House of Dionysos, Roman, late 2nd – early 3rd C AD, Nea Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

Saranda Kolones Castle, 12th C AD, Nea Paphos, Cyprus

-

-

alley restaurant, Lefkosia, Turkish Cyprus

-

-

Selimiye Mosque (St Sophia Cathedral), 1208-1326, Lefkosia, Turkish Cyprus